Jacob Harms Cornelsen of Rosenort, Manitoba enlisted in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force on April 1, 1916, at seventeen years old. After his training, his Battalion sailed to England in November 1916 and once overseas, he was sent to the 46th Battalion to serve in France, arriving there on February 2, 1917. Jacob was wounded by artillery shellfire three months later, on the night of May 3-4, 1917, about six kilometers north of Vimy Ridge. He had been part of the defensive line that was held after the ridge was taken in the famous Battle of Vimy Ridge a month earlier. Cornelsen died of his injuries on May 4, 1917.

Mennonites have long said “no” to war and Mennonite Heritage Village’s (MHV) recent exhibit, “Mennonites at War,” explored the topics of war and peace, and the Mennonite responses to them over their nearly 500-year history. I recently walked into the gallery to consider which artefact I should choose to highlight on Remembrance Day. Out of all the possibilities, I chose an envelope and two hand-written letters belonging to Cornelsen. In part, I chose these artefacts for Remembrance Day because they are rare. Mennonites in Canada were exempt from military service as a religious group during the First World War, therefore Mennonites were not forced to join the war effort. In fact, just over one hundred Russian-descendant Mennonite men from the prairies enlisted for military service during the war. Despite this, Cornelsen volunteered to serve and even lied about his age to do so, stating on his Attestation Paper that he was born in 1897, rather than 1898.

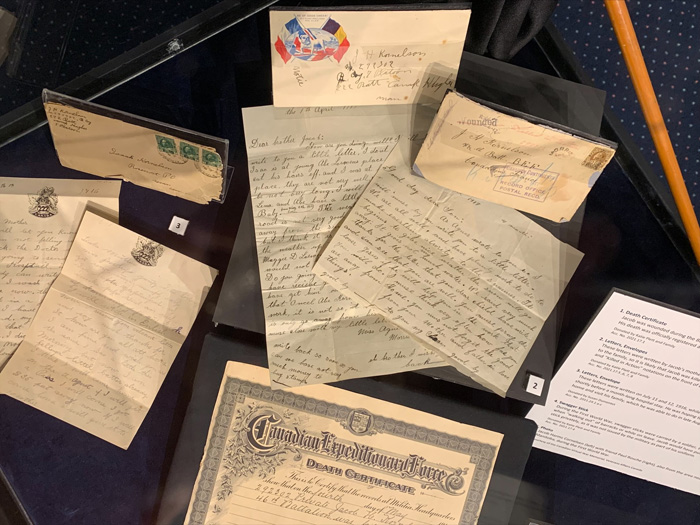

It is the human element of the story behind these artefacts, however, that are the main reason they stick out in my mind. The two letters were written to Cornelsen by his younger sister and his mother. Both letters are dated April 1, 1917 and are folded in an intricate way so that both would fit into the same envelope, thus saving on the cost of postage. The letters made their way through the military postal system, but they arrived too late and Cornelsen, who was killed in action just over a month later, likely never read them. We know this because the envelope is stamped “Wounded” in the upper left corner and then that marking is cross out and “Killed in Action” hand-written beside it. The letter would have meandered its way back through the postal system from war-torn France and been returned to Cornelsen’s mother in Rosenort. It is a weighty question to consider what it must have felt like for her, holding these unopened letters to her son in her hands again. We do know that she kept them her entire life and then handed them down to her daughter, Cornelsen’s sister, for safekeeping. Cornelsen’s niece continued to save the letters, envelope, and other items, including her uncle’s official Death Certificate, and then donated them to MHV in spring 2021.

On Remembrance Day, we remember the lives and sacrifices of the men and women who have served in Canada’s military. While Jacob Cornelsen’s letters fit perfectly into this theme, however, it is worth considering them alongside the dozens of other artefacts in the exhibit. A replica of the tongue screw that was used on Maeyken Wens when she was burned at the stake in 1537 for her Anabaptist faith, including the belief that Christians should love their enemies and not use violence against them, is displayed in one area of the exhibit. A leather jacket worn by Almon Reimer on a train ride in which he, conspicuous as a conscientious objector (CO) in a train car full of soldiers, reported for CO duty is displayed in a final area of the exhibit.

Taken together, Cornelsen’s letters, Wens’ tongue screw, and Reimer’s jacket, along with all the other stories contained in the exhibit, challenge us to examine this question of war and violence from a variety of perspectives. They highlight the complexity of war and how we remember its enormous cost, paid by millions of people – soldiers, civilians, and those left at home – throughout history and continuing around the world today.