“Mennonite Reflections: Arriving in Manitoba 150 Years Ago” is the exhibit currently featured in the Gerhard Ens Gallery. The following is the first in a series of articles highlighting each of the seven themes presented in this exhibit.

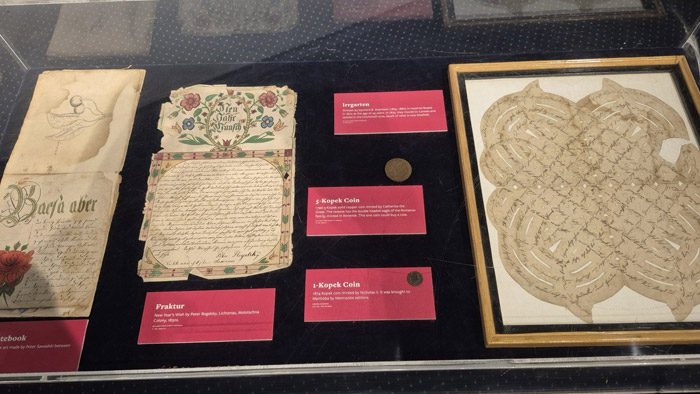

For centuries, Low-German Mennonites have migrated to various countries, their primary motivation being maintaining their faith and traditions. In the 1780s, Catherine the Great invited Mennonites in Prussia, among others, to settle in “South Russia” (now Ukraine). She promised special privileges, offering them an opportunity to live and worship as they desired.

By the mid-19th century, Imperial Russia, led by Czar Alexander II, aimed to modernize and Russify the Empire following their defeat in the Crimean War. The Mennonites, previously living in relative isolation and under the guardianship committee which oversaw their day-to-day governance, were to be integrated into the Empire, which would mean significant changes to their way of life. One major change instituted across the Empire was the abolition of the colonist category, which included the Mennonites. This loss of administrative rights meant that their unique integration of religious and secular administration was undermined, leading to concerns about maintaining their traditional way of life.

Another institutional change was the impending loss of their military service exemption. Historically, Mennonites were pacifists, and their religious beliefs prohibited participation in military activities. Negotiations with the Russian State proposed alternative service, but many Mennonites, particularly in the Fuerstenland settlement and the Chortitza Colony, along with the Bergthal Colony, and the Kleine Gemeinde, refused to discuss the issue. They demanded a full exemption from military service or sought opportunities elsewhere. This steadfast refusal highlighted the importance of their religious convictions and the lengths they were willing to go to preserve them.

These Great Reforms, initiated by the Russian government in 1869, also included efforts to diminish the Mennonites’ control over their German-language schools and other cultural institutions. Fearing the loss of their religious and educational autonomy, along with economic issues, the more traditionalist Mennonite groups decided it was time to move again.

As Mennonites sought new opportunities, the Canadian and American governments were also looking for settlers to develop their vast hinterlands. Although emigration from Russia was complex and fraught with bureaucratic challenges, the abolition of the colonist category and the granting of individual land rights facilitated their migration. Previously, land was owned communally, but the new system allowed Mennonites to buy and sell land individually, making it easier to leave.

Between 1874 and 1880, approximately one-third of the Mennonites in Russia emigrated to North America. This significant migration saw about 7,000 individuals from the Kleine Gemeinde, Bergthaler, and Old Colony groups settle in Manitoba. The promise of religious freedom, exemption from military service, and the economic opportunity to establish their own bloc of communities in a new land attracted these settlers to the Canadian prairies.

The next article in the exhibit series will focus on Manitoba as it was in 1870, just prior to the Mennonites arriving in 1874.