Village News

Neighbours: A Mosaic of Cultures

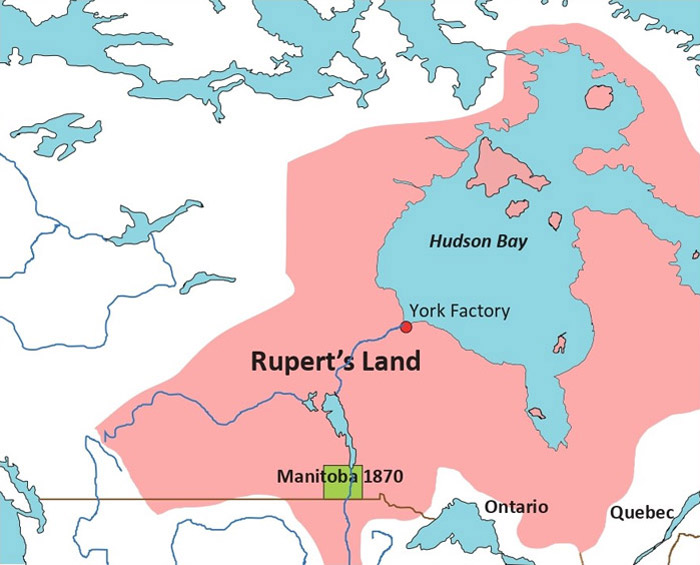

The Manitoba demographics census of 1870 provides a window into what Manitoba looked liked just three short years before the arrival of the Mennonite delegates in 1873. Manitoba had undergone turmoil as it evolved from the holdings of the Hudson Bay Company to a Canadian province in 1870. The Manitoba of 1870 was nicknamed “the postage stamp province” due to its modest size, spanning roughly 210 kilometres east to west and about 180 miles from north to south, a fraction of its present-day area. At that time, the population was 12,228.

The 1870 census report consisted of 5 districts made up of Church of England and Catholic parishes. The language spoken was either French or English, almost in equal numbers (strange tongues for the arriving Mennonites). There were 422 born in the British Isles, 60 from Canada, 118 from Ontario, 111 from Quebec, 166 Americans, and a smattering from elsewhere, with 11,298 born in the North West and Manitoba. This was soon to change.

Sir John A. Macdonald’s goal had been to integrate the new province into the Dominion by allotting lands to the existing populations in order to open the remaining land for settlement. The Manitoba Act granted 1.4 million acres of land and river lots to the Metis, and Treaty One provided small Reserves for the First Nations. The eradication of the bison had turned the Metis into sedentary farming people, day labourers, and draymen, with many having left for the west and the northern prairies of the United States. According to the Treaties, First Nations people were to be moved onto lands designated as Reserves.

These actions had left a vast prairie open for settlement, a tempting situation for American Manifest Destiny expansionism from the south. Macdonald, recognizing the dangers to Canada if this occurred, looked to immigration to ensure the prairies would remain Canadian. While Macdonald preferred immigration of British stock, in a pinch he would bring in ethic-religious groups who would be assimilated later.

Macdonald looked to establish settlements based on bloc settlement patterns, also as a means of keeping them apart and reducing any friction between groups. The government recruited agents who would travel Europe looking for potential immigrants and then join those immigrants on exploration trips to the former HBC landholdings.

In 1873 the Mennonite delegates who came to examine the lands encountered settlements and individuals who were farming the land. The area around Portage La Prairie raised some excitement with the delegation, as did the discovery by the delegates of settlers in the Clearsprings settlement close to the lands of the proposed East Reserve.

Macdonald’s success could also be seen by the 1871 census. The population had bloomed to 25,228. By 1881, near the end of the first wave of Kanadier Mennonite immigrants, the population had grown to 62,260, of which about 7000 were Mennonite. By the next census in 1891 it reached 152,506. A short decade later in the new century, Manitoba’s population had risen to 255,211 as many other ethnic groups from Europe arrived in Manitoba. But most of all, the 1870s had seen a major influx from the English-speaking members of the Ontario Orange Order who soon became the leaders of the Manitoba establishment. In less than one generation the Manitoba of pre-confederation was no more.

The decade of the 1870s was what W.L Morton referred to in his book Manitoba: A History as “The Triumph of Ontario Democracy”. This decade forever changed the demographics of Manitoba. The influx of Anglo-Saxons: Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists from Eastern Canada was forever to shift power.