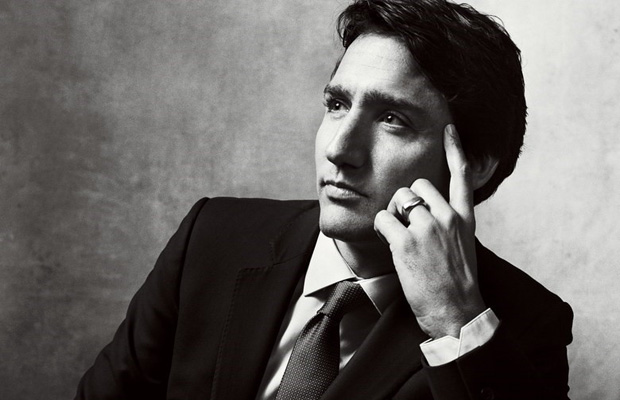

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been criticized rightly about his recent false claims that Canadian women have a constitutional right to abortion (fact check: Canada’s Charter does not set out such a right). Yet, Trudeau goes on to justify abortion because, according to Trudeau, women have “the right to control their own bodies.”

This justification should be criticized, too.

Why? Because it’s absurd.

Trudeau’s justification of abortion works only if the following argument works (I call it the body-part-control argument):

- Premise 1: Every woman has the right to control her own body.

- Premise 2: The fetus is a part of the pregnant woman’s body.

- Conclusion: Women have the right to abortion.

The argument sounds good, but is it sound?

Nope, it is NOT sound. Consider the following reasoning.

First, assume (for the sake of argument) that the second premise is true. That is, assume that the fetus is a part of the pregnant woman’s body.

Second, consider the logical relation of transitivity. If A is a part of B, and B is a part of C, then A is a part of C. If a brick is part of a wall, and the wall is part of a house, then the brick is part of that house.

Third, keep in mind two facts: (1) a woman has two feet; and (2) a fetus has two feet.

Now, consider the following: if a fetus’ two feet are a part of the fetus, and if the fetus is a part of a pregnant woman, then the fetus’ two feet are a part of that woman. Hence, the woman has four feet.

Now, also consider the fact that the male fetus has a penis. If the penis is a part of the fetus, and if the fetus is a part of the pregnant woman, then the woman has a penis. (Note: We’re not talking intersex here, we’re talking about a pregnant woman.)

Think, too, about the possibility of male triplets.

Since absurdities follow logically from the assumed truth of the second premise, we can conclude that the second premise is false. (This is a reductio ad absurdum argument.)

Significantly, premise 2 fails to recognize the distinction between the concepts of part and connection. An object A can be connected to object B, yet object A need not be a part of B. The piano in a mover’s truck is connected (via straps, etc.) to the truck, yet the piano is not a part of that truck. Similarly, the fetus is connected to a woman’s body, yet the fetus is not a part of the woman’s body.

Sure, every woman has the right to control her own body. But there are two bodies involved in an abortion.

Dear Prime Minister Trudeau: Please notice that it’s one thing to control one’s own body – it’s quite another to kill the body of another!

Postscript: An objection and a reply

Objection: In 2014 there was a case in China of a baby conjoined at the torso to a headless parasitic twin, so the baby had extra legs, arms, etc. This case counts against the alleged absurdity of a woman having more than two feet or two hands (e.g., eight of each) and so on (e.g., three penises). So the above critique of the body-part-control argument fails.

Reply: Nope, it’s the objection that fails. Why? Because the limbs etc. of the headless parasitic twin are ATTACHED to the baby, but are NOT PART of the baby – they are properly a part of the headless parasitic twin that’s conjoined / connected to the baby. To think otherwise is to continue confusing / not distinguishing the notions of ‘part of X’ and ‘connection to X.’ (Happily, the limbs etc. of the headless parasitic twin were successfully detached surgically from the baby.)

Hendrik van der Breggen, PhD, is a retired philosophy professor who lives in Steinbach, Manitoba.