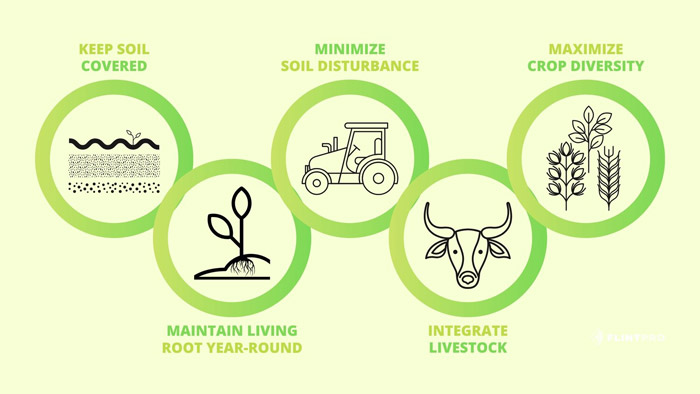

Regenerative agriculture is the new organic agriculture in my opinion. In organic agriculture, the list of prohibitions is long and the list of what to do is absent. In regenerative agriculture, the list of prohibitions is absent and the list of principles of practise is short, specific and practical. This list ensures that the soil, which is the foundation of all things living, will improve over time.

Principle 1. Minimize tillage. The soil is a living, breathing structure. Tillage is like ripping the roof off a house. Healthy soil has pathways and aeration systems formed by soil particles stuck together in beneficial structures, niches developed by worms, insects and other small creatures to create a comfortable environment for themselves, long threads of mycorrhiza extending the root system of plants and connecting them to phosphorous.

Principle 2. Keep the soil always covered with plant material. Mother Nature doesn’t like to be naked, but she is certainly not sexually repressed. Keeping the soil covered reduces or eliminates erosion which is still a major cause of soil degradation worldwide. Plant material on the surface of the soil reduces the impact of rain drops thus allowing more of the rain to soak into the soil rather than puddle on top of it.

Principle 3. While keeping the soil covered, try to provide living roots as long as possible throughout the year. In Manitoba we have a long cold winter which shuts down much of the soils activity, however perennial plants start as soon as the ground thaws and continue to grow till freeze up in the fall (at least 6 months and maybe longer) whereas annual crops like wheat and canola only have living roots for 3 months of the year. The reason you want living roots is that a living plant will exude sugars and carbohydrates into the soil, feeding micro-organisms in exchange for nutrients and other services. When there are no living roots the micro-organisms have less to eat.

Principle 4. Provide as much diversity as possible. This follows from Principle 3, where we saw that a diversity of crops such as perennials and annuals benefit the soil. The other thing to think about is where do beneficial pollinator insects like bees, wasps, butterflies and flies get their food from if there is only one type of flower for a very short time. I accompanied Dr. Doug Cattani on a field trip where he was documenting which native plants bloomed when in Manitoba. He found that something is blooming from earliest spring till the first frosts in fall.

A diversity of crops provides a farmer with risk management opportunities. If you have only canola on your farm and the weather is not suitable or the price goes down you have no alternative to rely on. If, on the other hand, you had some perennial forage for seed production or hay harvest for grazing, some cool season annual broadleaf crops like canola, peas, or flax, some cool season annual grass crops like wheat, oats or barley, some winter annual crops like fall rye or winter wheat, some warm season broadleaf crops like soybeans, some warm season grass crops like corn, some long season crops like sunflower, your risk would be wisely spread out.

Principle 5. Livestock integration. If you grow only crops continually, you will run short of nutrients and you will have more weeds than you want, whereas livestock in your cropping system breaks the weed cycle. Cows love to eat flowering dandelions. Ruminant animals will also recycle the phosphorous and make it available to the following crop.

The principle of keeping your soil covered all the time means that you are seeding more than just your main crop. This costs money, but one way of reducing the cost, or even providing profit, is to graze ruminant animals before a crop is established, after a crop is harvested, or dedicating a whole year to a cover crop or a perennial for grazing.

I spoke to a local dairy farmer that has been practising regenerative agriculture since before the term was coined and he says much of his land has 10% organic matter. The average Manitoba crop land has 2-7%. Each one percent of organic matter can provide ten pounds of nitrogen for the crop. So my friend the dairy farmer is getting (10% times 10 pounds equals) 100 pounds of nitrogen for his growing crop. Nitrogen that he doesn’t have to buy. Nitrogen that doesn’t release greenhouse gases in its production.