Beginning in 1874, Mennonites emigrated to Canada to safeguard their way of life, which faced threats in Imperial Russia. Upon arrival, they endeavored to rebuild a society that mirrored the one they had left behind. This migration allowed them to preserve their cultural heritage, religious beliefs, and communal lifestyle in a new environment.

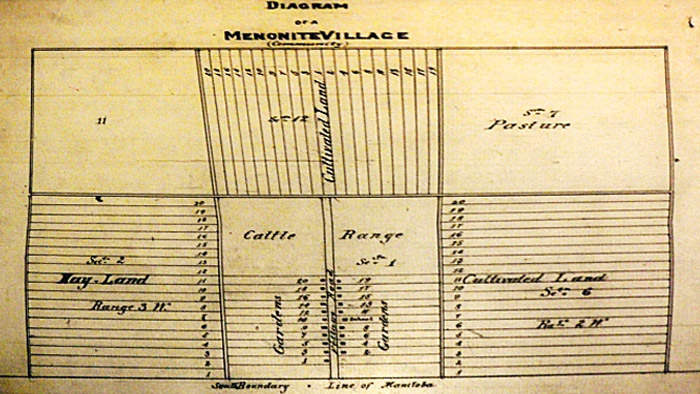

The Canadian government permitted Mennonites to settle in villages instead of isolated quarter sections, allowing them to recreate the familiar village structure of their former homeland. These villages typically featured a long central street, housebarns, strip fields, and shared pastures. Housebarns, an ancient home type from northern Europe, connected living spaces with animal stables, ensuring shared warmth during winters, animal safety, and efficient farm work. Summer kitchens were built nearby to keep houses cool during the warmer months. Examples of these housebarns can be seen at the Mennonite Heritage Village (MHV) in Steinbach and at the Neubergthal National Historic Site near Altona.

In 1877, the Mennonites constructed a windmill in Steinbach, inspired by advanced European windmill technology. They built several windmills across Manitoba, some of which were purchased, dismantled, and moved from the Red River Settlement and reconstructed in the villages. These windmills played a crucial role in grinding grain and supporting the agricultural economy. However, windmills were soon replaced by more reliable steam-powered mills, which provided consistent power and increased efficiency in processing agricultural products.

Mennonite children attended school until the ages of 12-14, learning the Bible, reading, writing, arithmetic, and singing. The educational goal was to nurture children into becoming good Mennonite villagers. The emphasis on religious and moral education ensured that the younger generation would continue to uphold the community’s values and traditions.

Three church groups, including the Bergthaler, Kleine Gemeinde, and Old Colonists (later known as Reinlander), moved to Manitoba in the 1870s. Each group had its own bishop and aimed to guide schools and civic matters through religious principles. This religious leadership played a pivotal role in maintaining social cohesion and addressing community issues.

Influences from outside of the Mennonite communities led to some disagreements within the Mennonite groups. Questions arose over modernization, with some members wanting to maintain or even to revert to more traditional practices, such as singing by numbers, while others were comfortable with modernization. These debates highlighted the tension between preserving tradition and adapting to new societal contexts.

Initially, Mennonites established their own self-governance systems. However, as Manitoba developed, provincial authorities sought to introduce municipal governments within their villages. This situation mirrored the challenges faced in Imperial Russia, prompting various responses among Mennonites. Some chose not to participate in elections or council meetings, while others saw municipal government as an opportunity. These differing views led to a certain level of division within the community.

Economically, Mennonites were less divided. They had always engaged in the capitalist system in Imperial Russia, focusing on selling their crops and participating in the agricultural market. In Manitoba, they continued this approach, developing businesses to support agriculture. Although some communities preferred railways to be nearby rather than within their villages, they utilized the railway systems for economic growth. Steinbach, for example, wanted the railway nearby but not directly in the community. The railway enabled Mennonites to export crops and develop agricultural businesses.

The establishment of businesses such as mills, blacksmith shops, and general stores also contributed to the economic prosperity of Mennonite villages. These enterprises provided essential services and goods, fostering self-sufficiency and economic interdependence within the community.

Mennonites in Manitoba faced the same issues they encountered in Imperial Russia but adapted to a new context and government. Their efforts to preserve traditions, establish self-governance, and thrive economically highlight their resilience and adaptability. The legacy of their early settlements can still be observed in the cultural and architectural heritage of Mennonite communities in Manitoba today. By balancing tradition with adaptation, Mennonites have successfully maintained their unique identity while contributing to the broader Canadian society.

The larger society around the newly arrived Mennonite immigrants would likely have noticed these Mennonite distinctives:

- Language: Plautdietsch – archaic West Prussian German dialect

- Church: Lehramt – elected lay ministers read their sermons; singing in unison led by precentors

- School: Göthisch – in German with gothic handwriting not readable by society at large

- Village: Gewanndorf – medieval open-field strip farming characterized by village herdsman

- Inheritance: Waisenamt – equal inheritance for women; also served as an early credit union

- Fire insurance: Brandordnung – universal self-administered fire insurance

- Foods: Borscht, Wrennitje, Rollküake, Plumemoos, Tweeback, Schnetje, Tjieltje, Portzeltje