Village News

Mennonite-Made Clocks

The Curatorial Department at Mennonite Heritage Village (MHV) recently participated in a photo shoot. No, we didn’t get glamour shots of ourselves taken among the collection. A professional photographer came in and took photographs of our sixteen Mennonite-made clocks; i.e., our Kroeger, Hildebrandt, Lepp, and Mandtler clocks. This was in conjunction with A Virtual Collection of Mennonite Clocks, a project led by the estate of Arthur Kroeger, late Mennonite clock expert. This project is a continuation of the work that began with Arthur’s book Kroeger Clocks, published in 2012 (and available in MHV’s gift shop). A Virtual Collection aims to collect and compile as much information as possible about individual Mennonite clocks, starting with ones in southern Manitoba, with the goal of publishing this information online to make it “accessible to all who are interested in these iconic touchstones of Mennonite heritage.” The estate of Arthur Kroeger plans to launch this website in the fall of 2017.

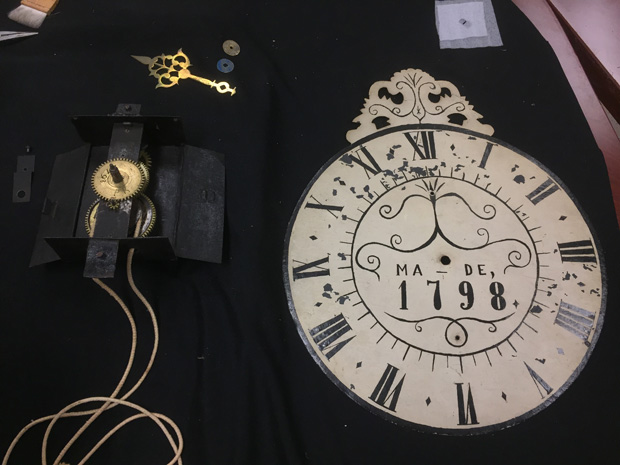

Mennonite clock-making tradition goes back to 18th century Prussia. The Kroeger family in Rosenthal, in what is now Ukraine, made most of the clocks that survive today. But Peter Lepp, Gerhard Hamm, and Kornelius Hildebrand (in the Chortitza colony) and the Mandtler family (in the Molotschna Colony) made distinctive wall clocks as well.

These clocks are an important part of Mennonite material culture. Parents often commissioned clocks as wedding gifts for their children. With regular maintenance and repair, they lasted a very long time, becoming heirlooms passed down through the generations. Despite being heavy and unwieldy, families still brought them along whenever and wherever they immigrated. There are Mennonite clocks now in Ukraine, Canada, the United States, Mexico, and South America. Even in a new country, these clocks helped make new houses feel like “home”. Many people recall their loud ticking and the bell that could be heard all through the house.

Taking part in A Virtual Collection has given MHV the opportunity to learn more about our collection of clocks, the way they work, and their individual histories. We took photographs of the clocks both with and without their faces, making visible the serial numbers and maker’s marks we did not previously know about. This information will go into our database for future reference. Before this photo shoot I had no idea how to set up a Kroeger clock. Now I’m not only able to install the pendulum and weights but can also take off the hands and face, adjust chains, and recognize different functions according to weights. For example, an alarm function requires extra weights, but a calendar function does not. Opportunities like this photo shoot give us the chance to engage in detail-oriented work related to artefacts in our collection and provide important professional development for us in the Curatorial Department.

Last, but certainly not least, our participation in A Virtual Collection will help make our clocks more accessible. Unless we have researchers using our collection for a project, public access to our collection is usually limited to exhibits. Since we do not have enough space to display all of our artefacts at one time, and constant switching of exhibits is expensive and time-consuming, we do not have the opportunity to showcase all the items in our collection. But once this website goes live, anyone with an internet connection and an interest will be able to learn everything we know about our clocks, helping us to fulfill MHV’s mission to “preserve and exhibit, for present and future generations, the experience and story of the Russian Mennonites and their contributions to Manitoba.”