Rethinking Lifestyle

Addressing Our Vulnerability

You can’t turn on the news these days without being inundated with stories of hurricane damage. Two weeks ago it was Harvey, and the damage was from flooding, more than it was from strong winds. Last week the news was about Irma. Irma’s damage came mostly as a direct result of the strong winds. I don’t know about you, but as I watch this, i have two emotions: one is compassion for the people affected, and the other thankfulness that we are not affected.

In this blog last week, Selena reminded us that Steinbach and much of south-eastern Manitoba is also vulnerable. She reminded us that south-eastern Manitoba is a productive, attractive area because swamps have been drained. Inevitably this means that whenever it rains, the constructed drains need to be able to handle the runoff if flooding is to be avoided. What happens when you get extra-ordinary amounts of rainfall as Huston did. You get flooding. The Harvey damage estimate is $180 billion.

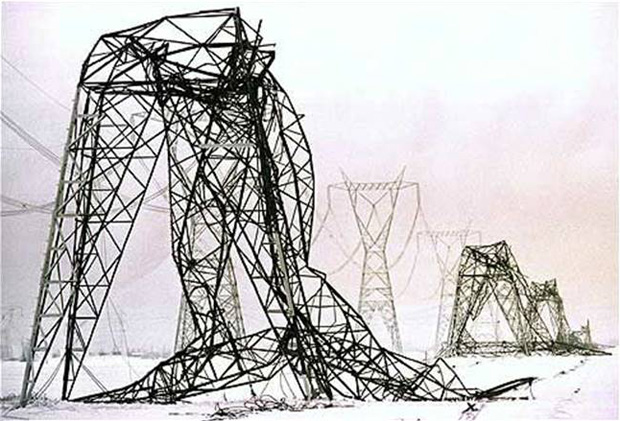

But it is not the danger of flooding that keeps me awake at night. What I think about is a failure of our electrical system. This system is vulnerable to a natural disaster such as the Quebec ice storm of 1998, and is even more vulnerable to failure as a result of a technical glitch such as the one that lead to the “Northeast blackout of 2003”. (Wikipedia provides a list of major power outages. The list is long. Although many failures are the result of weather events, many also are the result of technical failure.) The damage estimate of the Quebec Ice Storm is $5.4 billion.

These numbers – $180 billion and $5.4 billion – are so big that I have trouble comprehending what they mean.

The point is that when an unusual, devastating event occurs, the cost is massive. The cost is massive in terms of dollars, but even more massive in terms of disruption to human lives: deaths, homes destroyed, jobs lost, etc. Surely sensible people would be willing to spend just a fraction of that money to decrease our vulnerability.

We have a prime example of vulnerability reduction thinking in Winnipeg. In 1950, Winnipeg was devastated by a flood. This lead to the construction of the Red River Floodway. Because of the floodway, Winnipeg was not flooded in1997. Grand Forks, on the other hand, had not had the forward thinking politicians and was not spared

But the Floodway example is the exception. We do little to reduce our vulnerability to unusual events. The irony is that we could do much to reduce our vulnerability, and some vulnerability reduction costs very little. For example, we could build all new houses with an appropriate solar orientation; that is we build them with most windows are facing south. This is not a complete solution, but it contributes to a more complete solution and costs very little. Anyone building a home can decide to do this. Much better, of course, would be if our politicians would modify our building code, making such construction compulsory.

Of course we could do much more, both as individuals and as a community, to decrease our vulnerability. What I have suggested is just the most obvious. But we won’t do anything different as long as we assume that the “normal” we have experienced in the last number of years will continue – that there will be no exceptions to the “normal”. That is what the city planners in Huston had been doing.